Understanding The Federal Reserve Mandate To End Inflation

The Federal Reserve System, the nation’s central bank, has a dual mandate to pursue maximum employment and maintain price stability. These two priorities are currently treated equally, but that was not always the case. In fact, the Fed’s bias toward maximizing employment was a critical driver of the stagflation that plagued the U.S. in the late 1960s and 1970s. Recognizing the need to balance price stability and maximum employment, in 1977, Congress revised the Federal Reserve Act.

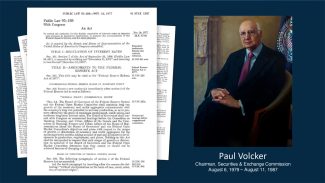

The Federal Reserve Act was enacted in 1913, in response to the Panic of 1907. The Act was revised in 1977 to direct the Fed "to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices and moderate long-term interest rates.” The 1977 revision of the Act was important, as it provided Chairman Paul Volcker with clear direction to end the Great Inflation, even at the cost of causing layoffs and throwing the economy into a recession.

It also explains why the Fed acted so decisively by hiking lending rates 12 times from March 2022 to July 2023. The Fed mandate compelled reversing the rapid rise in inflation that Americans experienced in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic and invasion of Ukraine, which led to U.S. sanctions on Russia and raised the price of oil.

Why has the Fed mandate been spelled out so explicitly in revisions to the Federal Reserve Act? Because inflation weakens economies and, if allowed to persist, has destabilized nations. The effects of inflation are especially insidious because inflation is a source of societal ills. Americans learned this painful lesson during the stagflation years of the 1970s, and after enduring a similar experience at the end of World War I and the Great Influenza. In 1919 and 1920, inflation averaged more than 15% per year.

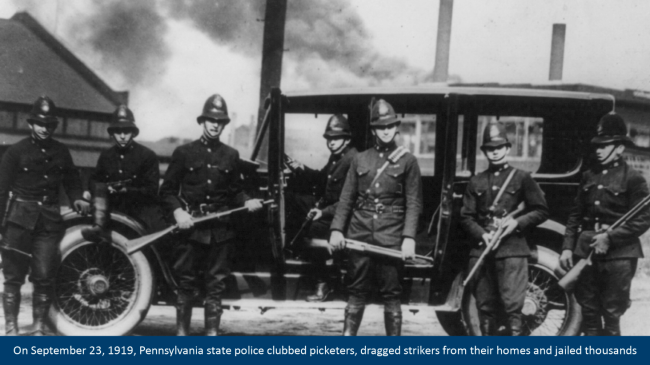

During these years, wages failed to keep pace with inflation, and labor strikes swept the nation, according to newspaper accounts. In some cases, strikes became violent. The photo above was taken during the Pennsylvania steel strike of 1919. Federal government inaction gave state and local authorities and the steel companies room to maneuver. On September 23, 1919, according to newspaper accounts, Pennsylvania state police clubbed picketers, dragged strikers from their homes and jailed thousands.

Although the inflation crisis of 2021 and 2022 was not as severe as in 1919, it was nonetheless dangerous because inflation psychology can wreck an economy. Particularly for the consumer-centered economy of the U.S., inflation is especially insidious because it erodes consumer buying power and that undermines confidence in the economy. The painful experience of the Great Inflation in the late 1960s and 1970s taught policymakers that it is critical to stop inflation from rising before it becomes entrenched in the American mass financial psyche.

The lessons learned from inflation crises inspired Congress to change the Fed’s legislative mandate in 1977, clarifying that maximum employment and price stability should be treated equally. In the post-Covid period, inflation is clearly the greater danger. The labor market has been very strong. It has given the Fed latitude to tighten monetary policy until inflation returns to its 2% target. This made it more likely that the US might enter a recession after the Fed hiked interest rates 12 times between March 2022 and July 2023, but slowing the economy was necessary to ensure long-term economic prosperity. Fortunately, inflation is now closer to the Fed’s target rate of 2% but the it’s important for investors to understand the balance the Fed has struggled to strike between its employment and inflation goals.